Hi @neptuak,

Good question! Now you’re getting more into the art verses the science. The research to answer that question is being done (Dr. Seiler @stephen.seiler is one of the people working on it) so there isn’t yet a true “based on research” answer. Which means any answer is based on a mix of experience and bias.

My bias, as you already know, is to favor doing low intensity work by heart rate vs power. So, I generally recommend keeping heart rate in the right range on those long rides - even aerobic threshold rides - and letting power be what it’s going to be. The main reason for my bias is that power is external and heart rate is internal. Heart rate is showing how your body is responding. So, if you let heart rate climb, you’re changing the nature of the ride.

But, I did discuss that with Dr Seiler and as I remember, he was more on the page of maintaining power for those slightly harder aerobic threshold rides and letting heart rate climb.

All that said, you are right that as heart rate climbs later in the ride, you are forcing IIa fibers to work aerobically and there are a lot of benefits to that for an endurance athlete. What I tend to do with my athletes is have them be pretty religious about staying in the heart rate zone through most of the base season. But, as they get towards the end of base and into the early part of the season, I do like them to do longer rides where they push the power as they are starting to fatigue. And I mean not only keeping power in it’s aerobic threshold zone, but to add some sweet spot work.

However, I don’t call that a base miles ride. That type of ride has a different purpose. While it still works base endurance, it brings in some race specificity (races are harder towards the end) and it also, as you smartly point out, gives those IIa fibers a hard aerobic workout.

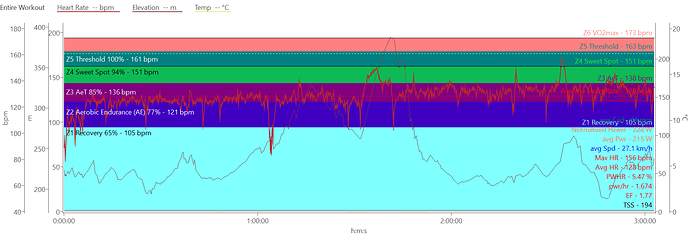

One last thing that may also help. I attached an image that I hope you can see. It’s an example of an aerobic threshold ride that an athlete I coach did a few years ago. His ranges are coded as colored rows behind his heart rate graph. Notice that he’s pretty consistently in the right range throughout the ride, but early on he’s at the lower end and towards the end he’s pushing the upper limit. So, he’s sticking to the right heart rate range, but still allowing some cardiac drift.

Thanks for the question!

Trevor