I really feel this episode needs a rebuttal. A lot of the ‘bad and ugly’ @trevor presented have nothing to do with CTL, and even his description of CTL was very lacking. Reminds me of a quote attributed to albert Einstein, “if you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.”

CTL is an aggregation of duration and intensity meant to be more useful than just miles(km), kilojoules, or hours over longer time frames. @chris said in the pod that knowing how it’s constructed is very helpful. That was just after Trevor’s explanation of CTL and the concepts it was based on. I’d argue that the concept is way more important and useful than the calculations, but if the calculations and concepts CTL is built on are useful Trevor should have presented them accurately.

I’ve often suspected Trevor has a bias against Coggan’s concepts and tools; his description of NP (normalized power) and its formula, while dismissive, wasn’t wrong (that I heard). His description of the calculations for TSS, absolutely was wrong. I don’t understand how he got it so wrong. He didn’t even mention IF and described the different training zones as being separately weighted ‘buckets’… that sounds like Bannister’s TRIMPS. the equation for TSS is actually very simple:

TSS = ((s x W x IF)/(FTP x 3600))x100

s: seconds. W:NP in watts. IF(intensity factor): NP/FTP.

A criticism the podcast made is that a TSS value doesn’t describe the nature of the training that was done with the implication that this fault continues downstream to CTL. There was the example of a “really slow” 4 hour ride accumulating 150-200TSS which is actually riding at ~62-72% of FTP which is a pretty big range smack in the meaningful part of zone 1 in the 3 zone polarized model compared to an interval session that accumulates 150 TSS in 1-1.5 hours. This is absurd and basically impossible unless your FTP is wildly underestimated. This was pointed out later in the podcast, as one of the drawbacks of CTL, that those values rely on an accurate FTP estimate but that has been the expectation since its inception. Coggan often says GIGO garbage in garbage out. And, it is a worthless argument, using miles per week means you need an accurate distance measurement so I guess that’s a major drawback to distance…

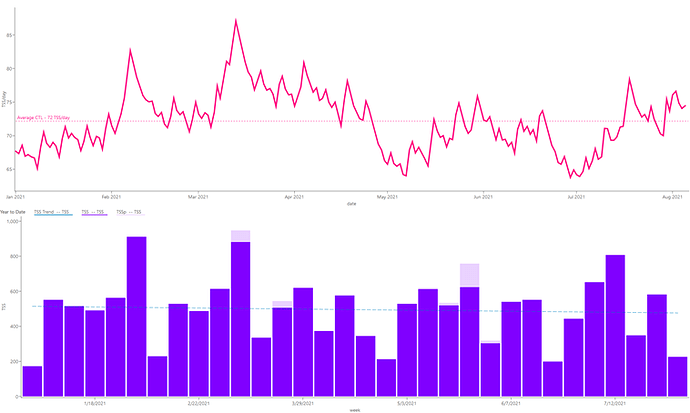

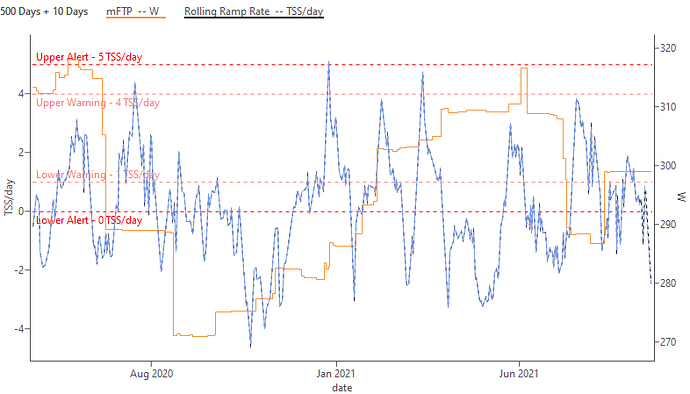

Is CTL being misused by athletes? Probably. Coaches? Yeah, probably. Trevor? Yes, unequivocally. any discussion of CTL and its benefits needs to include discussions about ramp rates and their impact and meaning as well as the rest of the PMC. An understanding of average and individually sustainable CTL ramp rates is very protective against non-functional overreaching or overtraining. Understanding how ATL(acute training load; basically the training load over the last week or how much fatigue the athlete is experiencing)drives changes in the CTL overtime and how it impacts performance short term. Or, TSB which is the relationship between ATL and CTL and is very predictive of athletes relative performance.

Really the PMC should be a single topic if the guys were trying to actually help listeners. The legitimate drawbacks of CTL presented are actually already addressed in the PMC. Teaching listeners how to use the tool as intended rather than portraying it as broken then not providing any hint of an improvement is pretty lazy. I’m pretty sure Trevor knows that too because he used it correctly when he was talking about his athlete who he trained to beat up on his buddies annual ride, he built the CTL up pretty high (80’s) then did a big dose of training to peak CTL (~90) (and ATL) then allowed both to drop as TSB came up. That is the classic peaking cycle described with a very useful concept.

joe