@smashsquatch, great question, and welcome to the forum! I’ve mentioned this before, but have had really good outcomes with splitting that time up with a split routine and riding 2x per day. Is it perfect? Not always. But I would recommend this over skipping sleep any day.

Coach Ryan

I was thinking about the multiple times per day thing a bit more. I remember reading/hearing that a fasted long ride and a non-fasted ride (even if eating) started to look similar from a physiological perspective after riding for a couple of hours. So could periodizing your nutrition (in this case, low glycogen availability) for shorter low-intensity rides increase the benefits gained from them? Is that benefit only fat metabolism or is it also for the other things like mitochondrial density)? I remember hearing how you should be careful and not do this often, but if your rides are always short, would it be preferential to try and have low glycogen when doing shorter Aerobic rides to gain increase benefit from them?

@smashsquatch This is just my experience with it, but I was doing 2x per day riding for months on end and saw drastic improvements in my fat oxidation (tested with a metabolic cart) and great performance improvements by focusing on doing the rides at the appropriate intensity regardless of fueling status. There were certainly some days where I might have missed breakfast getting out the door, but for the most part these were fueled rides where I consumed some kind of meal or snack before riding. At the very least, these rides did not have any type of fasting strategy built into them. You can enhance the improvements in that fat oxidation with a combination of dietary approaches and good training, but there is the risk of running out of fuel or limiting your ability to do high intensity if this is something practiced inappropriately.

To improve mitochondrial density, I always push for focusing on the appropriate intensity and duration rather than stacking a fasting strategy on top of a ride. Can it help? A bit, but I’m rather simple when it comes to the training - what’s going to give you the biggest bang for your buck? Let’s focus on that and do it well. Fasting becomes an additional piece of your training to manage for what, in my opinion, is a marginal gain. So long answer, I don’t feel that fasting, even with shorter rides, is preferential if you are performing good training and practicing good recovery.

Coach Ryan

Thanks for the feedback Ryan. Appreciate the thoughts around the fasted rides

After reviewing Trevor’s how to Low intensity ride, the one thing that pops up to me is how to target heart rate when doing split rides. For example, when doing a 40-90min ride, I can generally do it at a much higher power output than a ~2-3hr ride without seeing my heart rate climb into z3+. What’s the best way to approach this?

This raises the question about the value of those lower intensity rides where “appropriate duration” cannot be achieved.

The job time crunch means I can seldom train for more than 75 minutes on weekdays, and a combination of mental and trainer fatigue means I’m rarely able to push myself to sit on the trainer for more than 2 hours on the weekends.

Without venturing into a different training zone, is there any advantage in pushing intensity towards the upper reaches of Z1 on those 1 to 1.5h rides, where the focus isn’t on recovery, or is the ride so short that it has no effect anyway for someone with a reasonable level of fitness under the belt?

I’m in the same situation. Most of my rides are +/- 90 minutes either due to workday constraints or trainer-itis, there is a time limit I’m willing to sit on a bike and not actually go anywhere. Actually, I don’t usually take rides longer than 90 minutes on the weekends when the weather is good either due to family, house, and Dad duties.

Say I am currently doing my 1-2 workouts of FTP intervals a week, what is the concern with doing the other workouts (interval sets) slightly below Aerobic Threshold/LT1 power and heart rate? Would one be flirting with training in “no-man’s land?”

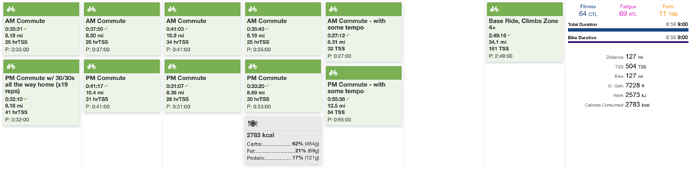

@smashsquatch and @CEBorduas, great questions. So referencing that build for the bikepacking trip, here’s a snip from one of my typical training weeks leading up to that, and it was exactly the 2x per day approach with a focus on how to ensure I can get an adaptation even though the appropriate duration cannot be achieved.

You’ll see that for the most part it’s just consistent riding, but if we dig into some of the rides, there are a couple things that stand out.

- I spent a lot more time in the upper end of zone 2 or into zone 3 (no man’s land). This is ok because that is still very much an “aerobic” training zone. It’s just going to require more recovery if done for a long time. The ~40-45 min rides weren’t long enough to string out recovery much more than overnight or a day.

- On sessions where the “feelings” were good to go hard, I’d go hard. So early in the week the PM session was a 30/30 all the way home where I was able to achieve 15 minutes just above threshold. The days in between were also based on feel and if the legs could turn over a larger gear, I’d push more into zone 3. If not, I’d keep it in zone 2.

- later in the week, once any fatigue was built in, I’d finish up with an achievable amount of tempo during both the AM and PM ride. Saturday was off, and then Sunday a reasonable length base ride with some harder climbing.

So to the questions of how to achieve this, I would suggest that you can get into that no man’s land at times to get the appropriate overload. Try not to be a slave to the Z1 threshold. This block referenced above was a 4 week block immediately preceding the bikepacking trip. Performance was stellar throughout and there was never a day where I felt like I needed to ride more or didn’t have the fitness. I might get slammed for suggesting going into that middle zone, but for us time-crunched athletes, I feel it is a completely reasonable place to spend some time in order to get adaptations.

Coach Ryan

I would agree. Having some level of capability in all zones is essential (or at least highly desirable). Who wants tools missing from in the shed. Coach Trevor gets a lot of grief for his current sprinting ability and I understand the likelihood of him winning a sprint is low. But I’m sure he would like to put that kid on the tricycle in his place given the opportunity. <I’m joking>

Not totally related; but, when I trained for 2 half marathons and I’m pretty sure most runs progressed from low tempo to VO2 by the end. Was it ideal? Probably not. I was blindly following the plan and running at a pace I felt “comfortable” with. Ultimately, it got me the result I was looking for.

BTW, after each race; I traded the trainers for cycling cleats and never wanted to run again.

![]()

I like the way you say it - tools missing from the shed. I like to apply this to cadence as well when working with athletes to have them become comfortable utilizing the entire spectrum of cadences.

I agree on the running progressions. Having coached marathoners in the past, we did a very similar progression and actually did quite a bit of pace runs that would have been in that no man’s land. The stuff works. It’s not for everybody, but it works.

Same here on running! Seems like every run in the past I would finish and say “never again”…until next time.

Coach Ryan

Thanks for sharing an example training week. It seems to me that there is something missing from the polarized approach. Remembering that it was developed by examining the habits of elite athletes for whom training is their job, we need to consider the time availability of the athlete. Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, the massive watts that a pro can produce means that it is simply too stressful for them to ride for extended durations in “no mans land.” Whereas, the average amateur may need a little more stimulus to cause an adaptation.

So that leads me to wonder whether the minimum effective dose to cause an aerobic system adaptation could be measured in, say, kJ’s? Is there some recovery marker that one could use to identify when the athlete is ready for a follow-on dose of aerobic training?

@SteveHerman, excellent point. I think it’s just about having a bunch of tools in your shed (to reference @Schils comment) and selecting the appropriate one for your needs. You make a great point about the polarized really being highlighted in elite level athletes. And yes, at the absolute powers and paces they are riding, running, rowing, etc. at, to have them ride in that middle zone probably doesn’t make a lot of sense due to the energy contributions required at those high absolute speeds. At the time of that example training week, there was no way I could have done “long” rides to prepare for that trip, so the only option was to bump the intensity to the middle and then hit it over and over and over again for a brief couple of weeks.

As such, for the rest of us, we might need to occasionally find ways to provide that overload to continue the adaptive process, and there are a lot of options out there. Interesting question about kJ’s to monitor. I’ve used that in the past with athletes, knowing what the demands of their events would be like. We’ve targeted certain levels of work (in kJ’s) to be completed during a ride at times and it was helpful because if they were riding slower, they would realize that it takes a lot more time to achieve a certain amount of work, and if they were riding harder, it would take less time, but might require more pacing during or recovery afterward. We know what our own “typical” rides would look like in terms of kJ’s by looking at historical data, so using that as one tool to promote our training can be helpful.

Good question on the recovery marker. Can you expand on that a bit? Is this a marker that you would use to know essentially when to push that aerobic training load further, perhaps by moving into some of the Z2 effort range? Maybe related: there was an interesting discussion on Fractional Utilization not long ago where there were some posts referencing a suggestion of a <10% difference between LT1 and LT2 as an indicator of when to incorporate higher intensity training. I was unable to find any research to support this, but it may just be something the authors from Uphill Athlete noticed in the lactate test results they were receiving from their athletes (my old lab used to do much of that testing for them, so I can see where the suggestion comes from). Since they focus very heavily on <LT1 training, this may be a novel way to indicate when you need more higher-end work.

Hope that helps!

Coach Ryan

Yeah, I guess what I was thinking in terms of a marker is like some kind of biomarker - a “thing” that can be measured to indicate recovery. It is a slightly nebulous idea, but I was thinking in terms of a decay constant. So we add a bolus of training, measured in kJ’s, and the body recovers from that training at a certain rate. The recovery would be measured by this marker. Once the marker reaches a critical value, another bolus of work could be added. Now that I’m expanding on it, it seems like what I am grasping at the CTL/ATL decay constant in the performance manager chart and whether there is some quantitative way that one could validate the number used in that model.

I’ll have to check out the fractional utilization thread. Thanks for the cue!

You are so right about being very careful about prescribing kJ’s. One can easily end up in a death spiral in pursuit of kJ’s because at a certain point it’s simply not possible to consistently accumulate significant work at harder and harder intensities. And of course, not all kJ’s are equal in terms of the energy demands. If we stipulate that the work must be achieved exclusively aerobically, we can make some progress.

That’s a good point. It seems like people are searching for this or something similar, so I guess we’ll have to see if any particular marker comes of it. Like you said, the accumulation of kJ’s (and work, which would impact CTL/ATL) are not all equal, so that’s the tricky part in finding some kind of a decay marker.

I’ve used submaximal testing to ascertain “readiness” in the past, but that of course takes some time and is not a readily available marker. But it seems to fit the bill to at least tell if someone is recovered adequately to take on more load.

hey guys, great thread. One thign i’ve noticed about this forum is that while the activity level may be lower than some other forums, the input is all top quality (signal to noise ratio is high). So keep it up.

One question about the recommendations. E.g., do one of this ride per week, one of this ride per week but only a few times, etc. What assumptions are those recommendations subject to? Because i would think that, depending on how the rest of your week is structured, you could potentially do as many long easy rides as you want. Or maybe not "as many as you want’ but as many as you can and be able to recover with no long-term detriment. Or is that not the case?

second, just a quick anecdote. I used to poopoo these types of guardrails about things like longer aet rides based on past experience. When i first started cycling tehse were the ONLY type of rides i did, and i was fine, so how could it be that you should only do them a couple times lest you overtrain? So i have been regularly going on hard MTB rides for many hours, thinking i’d be fine.

Anyway, lo and behold, the wheels just sort of fell off the bus this past week. I started training again after a rest week, and immediately could tell something was off. Felt tired, HRV is low, RHR is high, I had muscle pains in the legs for one day and chills at night the night before, even though i know i’m not sick because i’ve been isolated (so couldn’t have picked up a virus).

I feel a lot better now, although still not great and RHR is still through the roof. I think i should start training–sometimes it’s hard to tell for me if RHR will get better with rest, or it’s because i’m resting too much–but i only feel like training easy. My plan is to go on a few easy rides then start rebuilding, but do it much more carefully this time.

Thank you for the feedback! I’m glad to hear you’re enjoying the quality in the forum. We’re lucky to have a lot of great experts and community members to contribute to the many discussions.

I can relate to your previous training of operating outside of any particular guardrails. What I learned from it is that the adaptations came, but they were only to a certain point. Then there was a necessary change to the training in order to continue seeing progress. My experience was in exactly that - long MTB rides for many hours. It was good for some stuff (like long MTB rides for many hours  ), but not really that good for the MTB races I was entering.

), but not really that good for the MTB races I was entering.

To your question on the assumptions made when making recommendations - there are certainly boundaries that we either keep in our mental toolbox for things that seem to work and things that don’t seem to work. In addition, as we gain experience and test new concepts, we find the same thing - some things work better than others, and some things that “don’t” work for some people actually work for other athletes. So all of that, as generic as I’m making this sound (so it doesn’t get really long-winded), really helps to shape those assumptions, boundaries, guardrails, or whatever we want to call them over the years.

It sounds like you had an interesting experience lately when the wheels came off this past week. It’s always nice to have access to so much data (HRV, RHR, Power, etc.) because we can tell when we’re off. You didn’t happen to get a Covid vaccine recently did you? I’ve seen quite a few posts on some Facebook groups with people posting some pretty far-out physiological responses following their vaccine. Low power, very high HR, etc. Just a timely thought with all the vaccinations going on lately.

I think you’re taking a smart approach now - getting back into it slowly, especially if that’s what feels right intuitively. I would run with it. Again, having experienced something similar personally, it was hard to make that shift and start easy when I thought the only way to do it was to go hard. But you will be surprised if you can take a bit of a long-term approach and let those adaptations come gradually.

Thanks Ryan!

I appreciate the thought about taking the long-term view. I think for me, and maybe this is something for others to keep in mind also, that what that means is (a) go easier on the long rides, because the long hard rides (especially on the MTB side) can be super taxing, but also (b) build in more recovery in between rides and maybe plan on an 8 or 10 day schedule instead of a 7 day one.

How do you tend to do your MTB rides, in that case? It seems like one option is to be very disciplined about keeping them easy, but as we know, because of terrain (and excitement  ) this can be hard. So . . . do you sometimes just go as hard as you want, but be super discipilned about keeping the ride short?

) this can be hard. So . . . do you sometimes just go as hard as you want, but be super discipilned about keeping the ride short?

You’re welcome, @BikerBocker. Yes, I think those points are great - easier on the long rides and build in flexibility into your schedule. The 8-10 day schedule vs 7 day schedule can be a great way to block up your training and recovery periods.

Early in the season and through the spring I’ll try to do my MTB rides on terrain that will allow me to maintain the appropriate intensity “most” of the time. I know there will be points where the terrain will dictate more and I’ll do the absolute lowest possible effort to get through it, but at the expense of a higher HR/power response. It’s part of the deal though and I understand that if I can be disciplined for 80-90% of my ride on the dirt, it’s all good.

When we had our first kid and I was super time crunched I would have 1-2 days per week where I’d have barely 60 minutes to get out on the bike, and of course went straight to the trails since they were a perfect 10 min warm-up from the house. I’d go out and completely throttle myself for 45 minutes and then come back home. That was perfect for that time frame. The rest was easy riding indoors.

Now that I have more time and a better ability to structure the rides, I find that I’m doing less of that approach and more of the approach of scheduling those structured/disciplined long MTB rides. I’ll aim to push certain MTB rides to the longer end of the spectrum here and there, upwards of 5-7 hours. That way I’m forced into pacing myself! Aside from that, I’ll try to build around big days a few other moderately long rides where the legs aren’t feeling stellar and then will try to tune into the body, and similarly, not push too hard and try to remain more disciplined. It’s those days where the body feels absolutely stellar that it makes it hard to contain the excitement!

Thanks Ryan. I think i am finally starting to get it. Based on reading this response plus your previous responses in other threads and even (I think i recall) on the podcast, you HAVE sometimes done like, ultra-overload MTB rides in the past, but approached them as more of a capstone to a training block, or a “soul” ride for fun, rather than like a regular element of training.

Maybe that’s what i can do. Keep it generally controlled, endurance pace plus controlled intervals, and still occasionally do long, hard rides, but few of them, very infrequently, almost like a substitute for racing, and expect lots of rest afterwards.

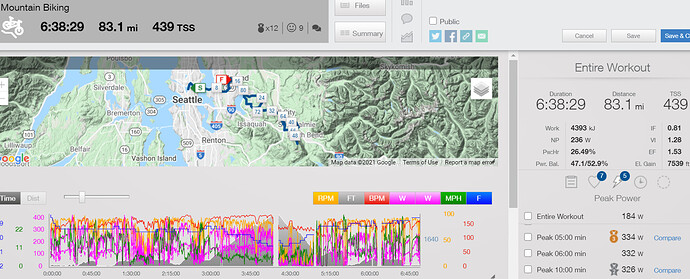

Like i did this ride last year:

and it absolutely smoked me. Season on pause for weeks afterwards.

But maybe the ride was only half the problem, and the rest of hte problem was: (i) what i did before, (ii) what i did after, (iii) what I tried (unsuccessfully) to do the week after, i.e. keep training as if nothing had happened

@BikerBocker, wow, what a ride! Impressive! Yes, that’s the kind of ride that I would look to do on the MTB as a soul ride or capstone type of ride. It’s fun, you can look forward to it, and then when you finish you can plan some good recovery to ensure you bounce back from it.

I like what you said about doing them as a substitute for racing. In terms of the big days like that, it will end up feeling kind of like a race because the training load will be so high and you should be cooked after it. And I completely agree - it’s all about what you do before it, after it, and then in the following days/weeks. That’s a great key point you made - with a ride like that, you can’t go right back into training as if nothing happened.

Excellent example, and this is why we do this stuff, right? We learn from it and then get better at integrating big rides like this into our calendar.

Thanks for sharing that one!

Ryan