Great conversation! I’ll admit that I wasn’t fully following all of the questions. I didn’t know what you meant by "saturating the cardiac response. But, I hope this adds to the conversation…

The key thing that comes to mind for me is the fact that while heart rate is a very useful internal metric, it’s an indirect metric. It’s used as a surrogate for VO2 because it’s a lot easier to measure on the road and the heart rate curve correlates with the VO2 curve. But it doesn’t correlate perfectly. VO2 and lactate are our better direct measures - we just can’t use them on the road. What we have is heart rate - which is great - just remember that the response you see isn’t always perfect. Particularly when you’re trying to get a perfect measure of oxygen utilization.

I point that out because in the situation you’re talking about here - comparing a very aerobic athlete to an anaerobic athlete when riding at threshold, the heart rate data, while helpful, can be a little deceiving and requires careful interpretation.

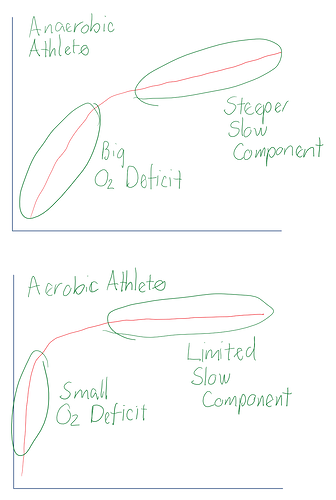

What drives heart rate is the level of fiber recruitment and more importantly, the mitochondrial activity within those fibers. With the anaerobic athlete, when they start putting out a big steady power, they’re going to initially recruit more type II fibers with low mitochondrial density. Which means there’s going to be a lower initial driver of heart rate and they’re going to have a bigger oxygen deficit. Then even after heart rate has finally fully responded, because they are still more reliant on fatigable fast twitch fibers, they’re going to see greater fiber recruitment and importantly, much more fiber cycling. Hence the much bigger slow component.

By contrast, the highly aerobically trained athlete is going to see much more mitochondrial involvement right from the start, so they’ll have a much smaller oxygen deficit. They’ll also be much more likely to level off around their true anaerobic threshold. They are going to be able to rely less on fast twitch fibers and so the slow component will also be much smaller. You’ll see their heart rate and VO2 level off much more than with the anaerobic athlete.

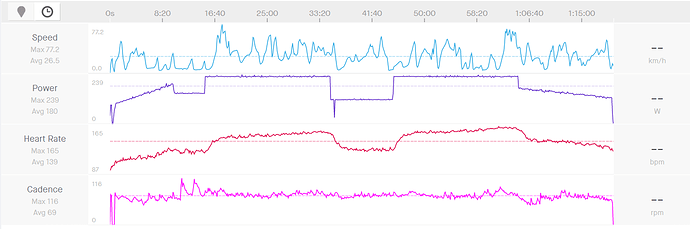

This is always hard to explains, so forgive my chicken scratch, but here’s a quick visual:

All of this means that it is easy to over-estimate the first athlete’s anaerobic threshold power and heart rate. While, estimating the highly aerobic athlete’s true aerobic threshold heart rate and power from something like a 20 minute test is much easier.

So ,often when the anaerobic athlete thinks they are doing threshold work, they are actually training well above their true anaerobic threshold. That’s why the effort puts a bigger strain on their ANS. But if you were able to identify their true anaerobic threshold and tell them to train at it, they’d find it frustratingly easy and want to go harder.

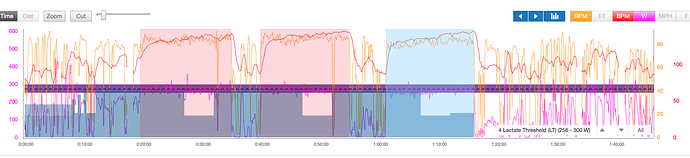

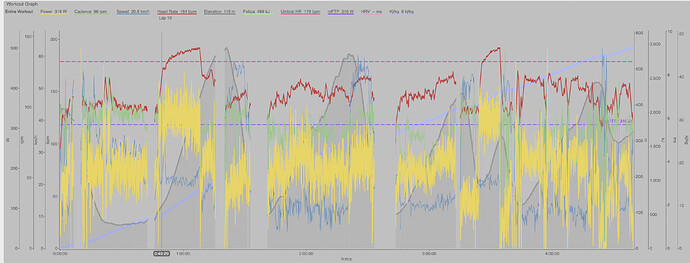

When I’m working with one of these athletes who’s anaerobically strong but aerobically weak, I’ll often have them do a big anaerobic effort before doing the intervals. The idea is to get them to clear out some of the anaerobic energy stores and then have them do a truer aerobic effort. There’s plenty of research backing this and also showing that with these athletes, if you’re using a 20 minute test to estimate FTP, an all-out five minute effort before the 20 minute test is necessary.

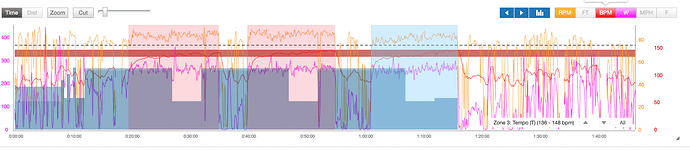

When I’m working with a strong aerobically trained athlete, I’m often more tempted to just give them straight threshold intervals because they’ll see the very rapid heart rate/VO2 response and they’ll tend towards their true anaerobic threshold. I don’t find there’s as big a need with them to deplete some of their anaerobic stores first.

Hope that helps!

Trevor